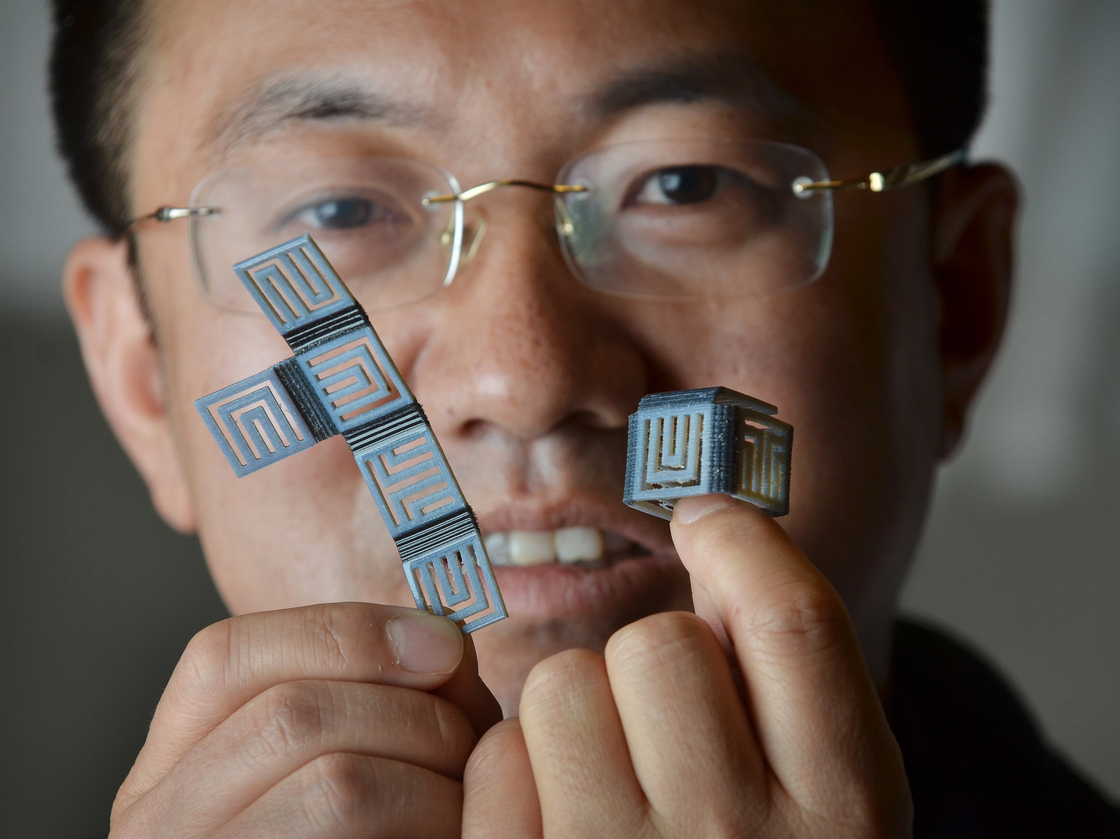

H. Jerry Qi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado University, holds simple models printed using polymers that have "shape memory." The flat piece on the left can reshape itself into a box with the application of heat.

Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado H. Jerry Qi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado University, holds simple models printed using polymers that have "shape memory." The flat piece on the left can reshape itself into a box with the application of heat.Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado

H. Jerry Qi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado University, holds simple models printed using polymers that have "shape memory." The flat piece on the left can reshape itself into a box with the application of heat.Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado In our Weekly Innovation series, we pick an interesting idea, design or product that you may not have heard of yet. Got an innovation you think we should feature? Fill out our form.

The advent of 3-D printing brought on a number of innovations worthy of news coverage. Printers have created prosthetic hands, action figures, food, even blood vessels, simply by depositing layer after layer of different kinds of ink.

Now a handful of engineers around the world are trying to push the boundaries one step further — by printing objects that can build themselves.

It's called 4-D printing, and the fourth dimension in this case is time. Here's how it works: A 3-D printer with extremely high resolution uses materials that can respond to outside stimuli, like heat or light, as ink. The resulting structure can change, move or even assemble itself after it's been printed.

One team of researchers led by H. Jerry Qi, an associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, is using heat and mechanical pressure to transform flat objects into three-dimensional structures. They printed an unfolded box with glassy polymer fibers — a composite material that has "shape memory behavior" — along the folds. They heated it, pulled on the sides and cooled it, and the flat structure responded by folding into a box.

Another team — a collaboration between University of Pittsburgh, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Harvard University — recently garnered an $855,000 grant from the U.S. Army Research Office to explore how adaptive materials can respond to stimuli like light or temperature.

It's not unlike how the body works, says Professor Anna Balazs at Pittsburgh. It responds continuously, in complex ways, to the world around it.

"The idea is the use the full arsenal of 3-D printing," she says. "It allows complicated objects to morph their structure. You're not just going to print one object, one use."

One potential application? You could make a fabric that changes color in response to light or changes permeability in response to temperature. It could provide a protective layer in the presence of toxic chemicals — that would be particularly useful for soldiers in combat.

Another application, Qi says, is useful in places where traditional manufacturing is impractical — like in space. You could make an instrument that's small and flat and expand it aboard a spacecraft.

You can't make these products at home, at least not yet. The printers are still being tested by individual academic labs, along with the responsive inks. Balazs says integrating the two for reliable commercial use will probably take another three to five years.

Until then, some researchers will be trying, as always, to take technology to the next level.

Skylar Tibbits, who researches self-assembly at MIT, is looking at how construction processes might be simplified by using materials that respond to shaking — or even to sound. His vision is lofty, but he has arguably the most imaginative ideas of 4-D printing research so far.

"Manufacturing could be more like growing," he said in a BBC interview in July. "Maybe the construction sites in the future, we play Beethoven and structures build themselves."

You can help select a name for the National Zoo's new panda cub.Abby Wood/Smithsonian's National Zoo

You can help select a name for the National Zoo's new panda cub.Abby Wood/Smithsonian's National Zoo  Mirrors erected on a Norwegian mountainside reflect sunlight onto the town below, which is cut off from direct sunlight for about six months a year.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov

Mirrors erected on a Norwegian mountainside reflect sunlight onto the town below, which is cut off from direct sunlight for about six months a year.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov  People gather in the central square of Rjukan, Norway, on Wednesday to bask in the sun reflected by mirrors on a nearby mountainside.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov

People gather in the central square of Rjukan, Norway, on Wednesday to bask in the sun reflected by mirrors on a nearby mountainside.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov

The brewers at Scratch Brewing Company add wild plants like spicebush, goldenseal, wild ginger, chanterelles and wild rose root to their beer to give it the flavor of the Illinois woods.Aaron Kleidon/Scratch Brewing Company

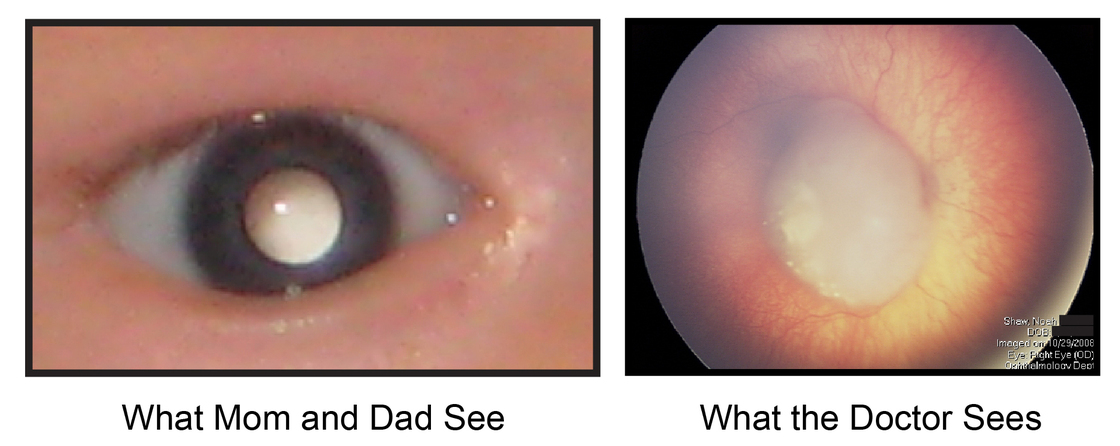

The brewers at Scratch Brewing Company add wild plants like spicebush, goldenseal, wild ginger, chanterelles and wild rose root to their beer to give it the flavor of the Illinois woods.Aaron Kleidon/Scratch Brewing Company  A milky eye can be a sign of early cancer of the retina.Courtesy of Bryan Shaw

A milky eye can be a sign of early cancer of the retina.Courtesy of Bryan Shaw