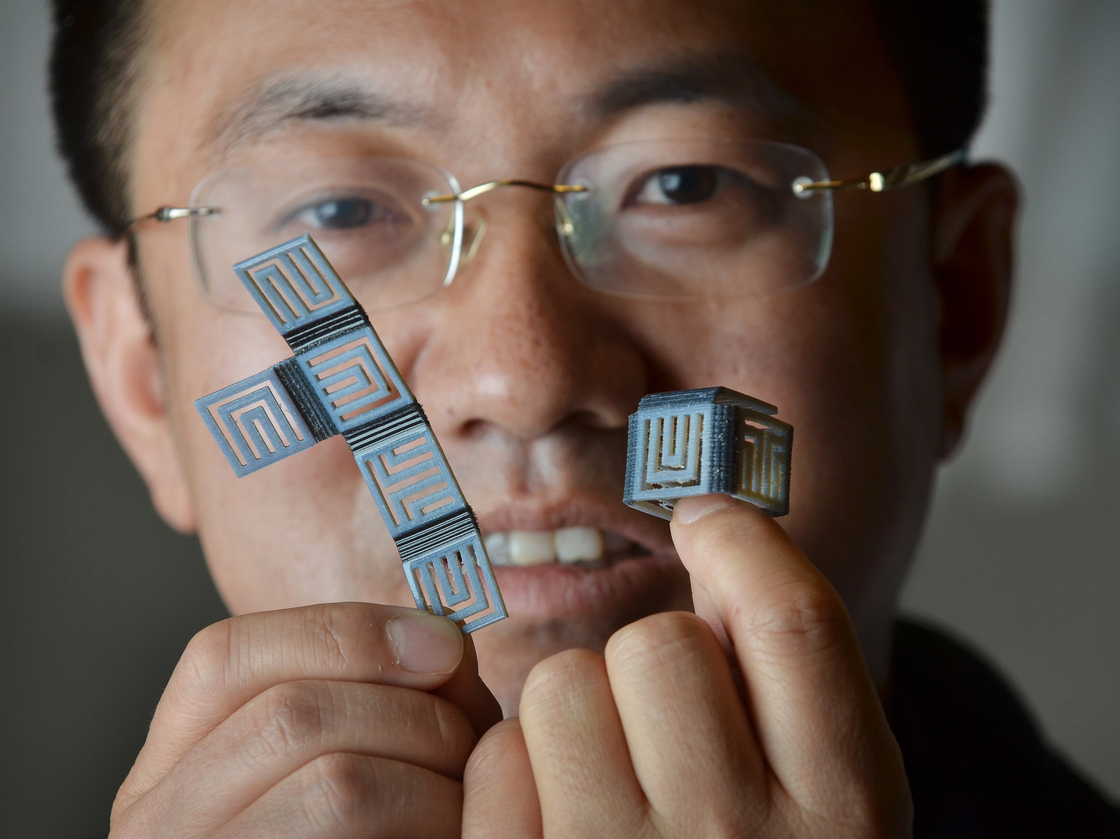

H. Jerry Qi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado University, holds simple models printed using polymers that have "shape memory." The flat piece on the left can reshape itself into a box with the application of heat.

Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado H. Jerry Qi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado University, holds simple models printed using polymers that have "shape memory." The flat piece on the left can reshape itself into a box with the application of heat.Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado

H. Jerry Qi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado University, holds simple models printed using polymers that have "shape memory." The flat piece on the left can reshape itself into a box with the application of heat.Glenn J. Asakawa/University of Colorado In our Weekly Innovation series, we pick an interesting idea, design or product that you may not have heard of yet. Got an innovation you think we should feature? Fill out our form.

The advent of 3-D printing brought on a number of innovations worthy of news coverage. Printers have created prosthetic hands, action figures, food, even blood vessels, simply by depositing layer after layer of different kinds of ink.

Now a handful of engineers around the world are trying to push the boundaries one step further — by printing objects that can build themselves.

It's called 4-D printing, and the fourth dimension in this case is time. Here's how it works: A 3-D printer with extremely high resolution uses materials that can respond to outside stimuli, like heat or light, as ink. The resulting structure can change, move or even assemble itself after it's been printed.

One team of researchers led by H. Jerry Qi, an associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, is using heat and mechanical pressure to transform flat objects into three-dimensional structures. They printed an unfolded box with glassy polymer fibers — a composite material that has "shape memory behavior" — along the folds. They heated it, pulled on the sides and cooled it, and the flat structure responded by folding into a box.

Another team — a collaboration between University of Pittsburgh, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Harvard University — recently garnered an $855,000 grant from the U.S. Army Research Office to explore how adaptive materials can respond to stimuli like light or temperature.

It's not unlike how the body works, says Professor Anna Balazs at Pittsburgh. It responds continuously, in complex ways, to the world around it.

"The idea is the use the full arsenal of 3-D printing," she says. "It allows complicated objects to morph their structure. You're not just going to print one object, one use."

One potential application? You could make a fabric that changes color in response to light or changes permeability in response to temperature. It could provide a protective layer in the presence of toxic chemicals — that would be particularly useful for soldiers in combat.

Another application, Qi says, is useful in places where traditional manufacturing is impractical — like in space. You could make an instrument that's small and flat and expand it aboard a spacecraft.

You can't make these products at home, at least not yet. The printers are still being tested by individual academic labs, along with the responsive inks. Balazs says integrating the two for reliable commercial use will probably take another three to five years.

Until then, some researchers will be trying, as always, to take technology to the next level.

Skylar Tibbits, who researches self-assembly at MIT, is looking at how construction processes might be simplified by using materials that respond to shaking — or even to sound. His vision is lofty, but he has arguably the most imaginative ideas of 4-D printing research so far.

"Manufacturing could be more like growing," he said in a BBC interview in July. "Maybe the construction sites in the future, we play Beethoven and structures build themselves."

You can help select a name for the National Zoo's new panda cub.Abby Wood/Smithsonian's National Zoo

You can help select a name for the National Zoo's new panda cub.Abby Wood/Smithsonian's National Zoo  Mirrors erected on a Norwegian mountainside reflect sunlight onto the town below, which is cut off from direct sunlight for about six months a year.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov

Mirrors erected on a Norwegian mountainside reflect sunlight onto the town below, which is cut off from direct sunlight for about six months a year.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov  People gather in the central square of Rjukan, Norway, on Wednesday to bask in the sun reflected by mirrors on a nearby mountainside.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov

People gather in the central square of Rjukan, Norway, on Wednesday to bask in the sun reflected by mirrors on a nearby mountainside.NTB Scanpix/Reuters/Landov

The brewers at Scratch Brewing Company add wild plants like spicebush, goldenseal, wild ginger, chanterelles and wild rose root to their beer to give it the flavor of the Illinois woods.Aaron Kleidon/Scratch Brewing Company

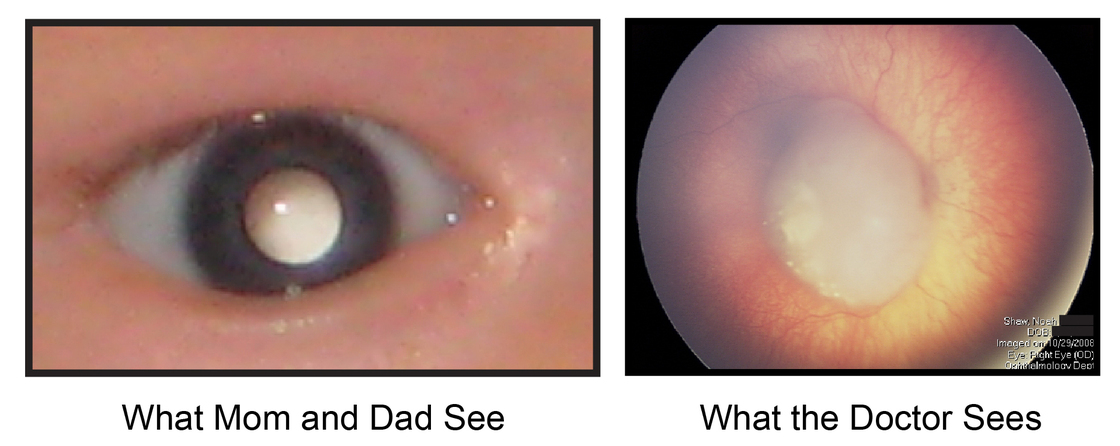

The brewers at Scratch Brewing Company add wild plants like spicebush, goldenseal, wild ginger, chanterelles and wild rose root to their beer to give it the flavor of the Illinois woods.Aaron Kleidon/Scratch Brewing Company  A milky eye can be a sign of early cancer of the retina.Courtesy of Bryan Shaw

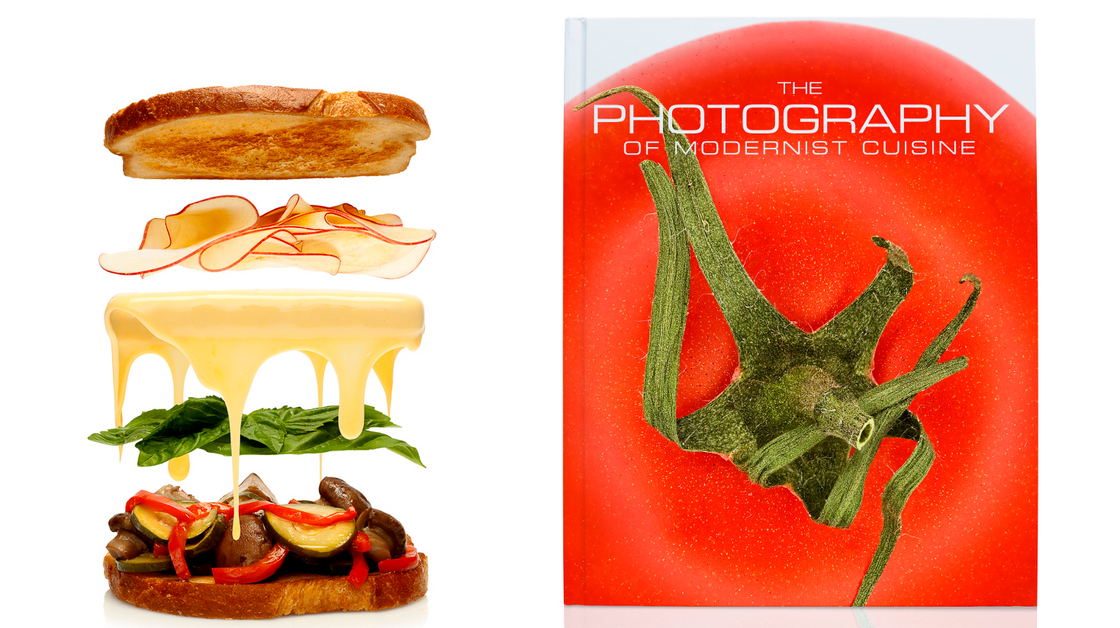

A milky eye can be a sign of early cancer of the retina.Courtesy of Bryan Shaw  Want to levitate a grilled ham and cheese in your next Instagram snapshot? The team at The Cooking Lab divulges their photo tricks in their new book.Courtesy of The Cooking Lab Look to the light: In restaurants, find a big window with diffuse, indirect lighting, Nathan Mryhold recommends. "If you have to use flash, use a napkin or menu to bounce the light off it and make it diffuse."Stand up: The angle at which we usually view dinner doesn't produce the best photographs. For food that's flat and wide, shoot the dish from right above. If the food is tall and narrow, get down low and shoot it from the side.Put it on black: Food is most dramatic sitting on white or black, says The Cooking Lab's Chris Hoover. "White can create some weird reflections, but black is quite easy shoot." Place the food black Plexiglass, he says. Then pin a sheet of black velvet on the wall to adsorb the light behind it.Dip your toe into editing: You don't need to buy a sophisticated editing tool, Hoover says. "Just get a basic program, like Adobe Lightroom," he suggests. "It's easy to understand, and there are tutorials on the web."Download an HDR app: For smartphone snapshots, use a high-dynamic range app, like TrueHDR, to capture all the colors and highlights of food.

Want to levitate a grilled ham and cheese in your next Instagram snapshot? The team at The Cooking Lab divulges their photo tricks in their new book.Courtesy of The Cooking Lab Look to the light: In restaurants, find a big window with diffuse, indirect lighting, Nathan Mryhold recommends. "If you have to use flash, use a napkin or menu to bounce the light off it and make it diffuse."Stand up: The angle at which we usually view dinner doesn't produce the best photographs. For food that's flat and wide, shoot the dish from right above. If the food is tall and narrow, get down low and shoot it from the side.Put it on black: Food is most dramatic sitting on white or black, says The Cooking Lab's Chris Hoover. "White can create some weird reflections, but black is quite easy shoot." Place the food black Plexiglass, he says. Then pin a sheet of black velvet on the wall to adsorb the light behind it.Dip your toe into editing: You don't need to buy a sophisticated editing tool, Hoover says. "Just get a basic program, like Adobe Lightroom," he suggests. "It's easy to understand, and there are tutorials on the web."Download an HDR app: For smartphone snapshots, use a high-dynamic range app, like TrueHDR, to capture all the colors and highlights of food. To capture the magic of grilling, the team at The Cooking Lab sawed a Weber grill in half and then combined 30 photographs together.Ryan Matthew Smith/Courtesy of The Cooking Lab

To capture the magic of grilling, the team at The Cooking Lab sawed a Weber grill in half and then combined 30 photographs together.Ryan Matthew Smith/Courtesy of The Cooking Lab

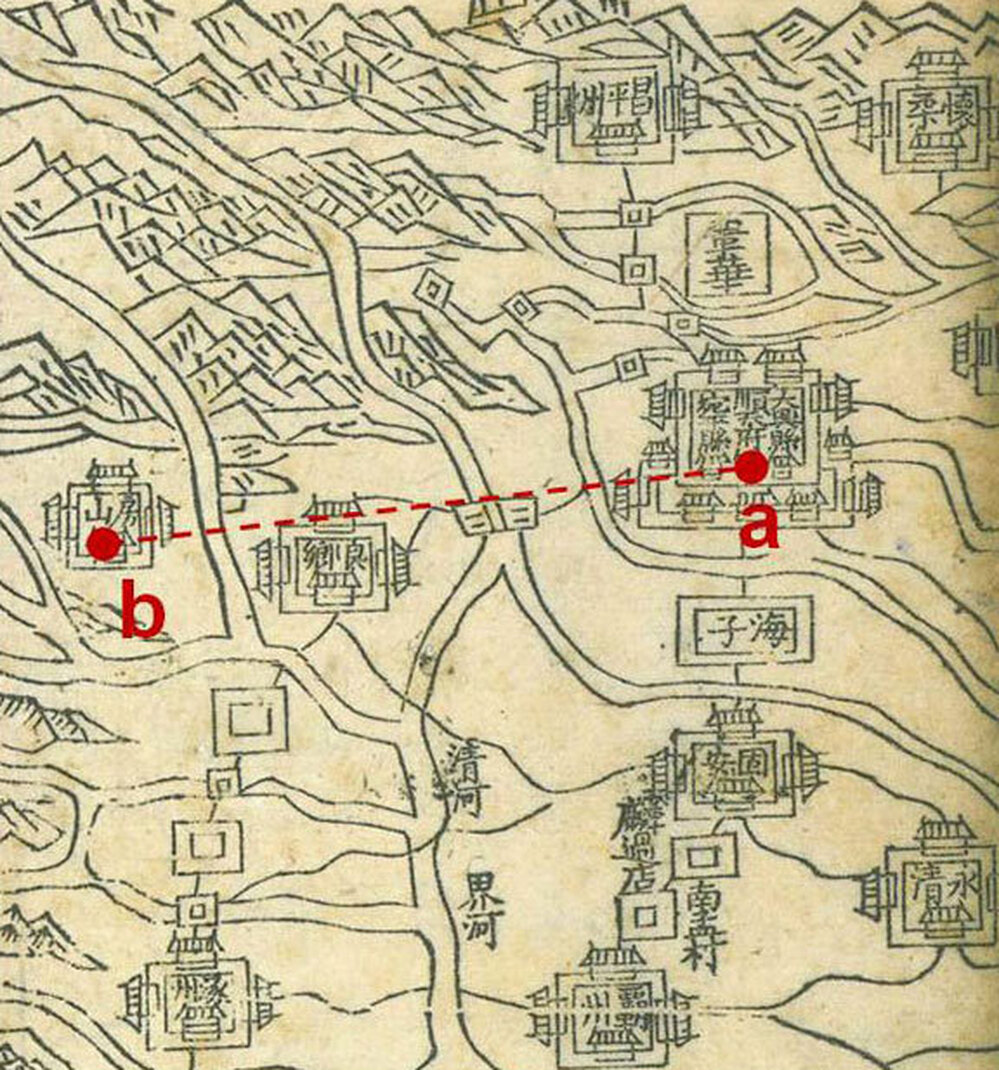

The distance between the Forbidden City in Beijing (a) and the Dasiwo Quarry in Fangshan (b) is about 43 miles. Double lines on the map represent rivers; single lines represent roads.PNAS

The distance between the Forbidden City in Beijing (a) and the Dasiwo Quarry in Fangshan (b) is about 43 miles. Double lines on the map represent rivers; single lines represent roads.PNAS  The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in Buxton, N.C., was moved almost 3,000 feet inland on July 9, 1999, to protect it from the advancing ocean.Bob Jordan/AP

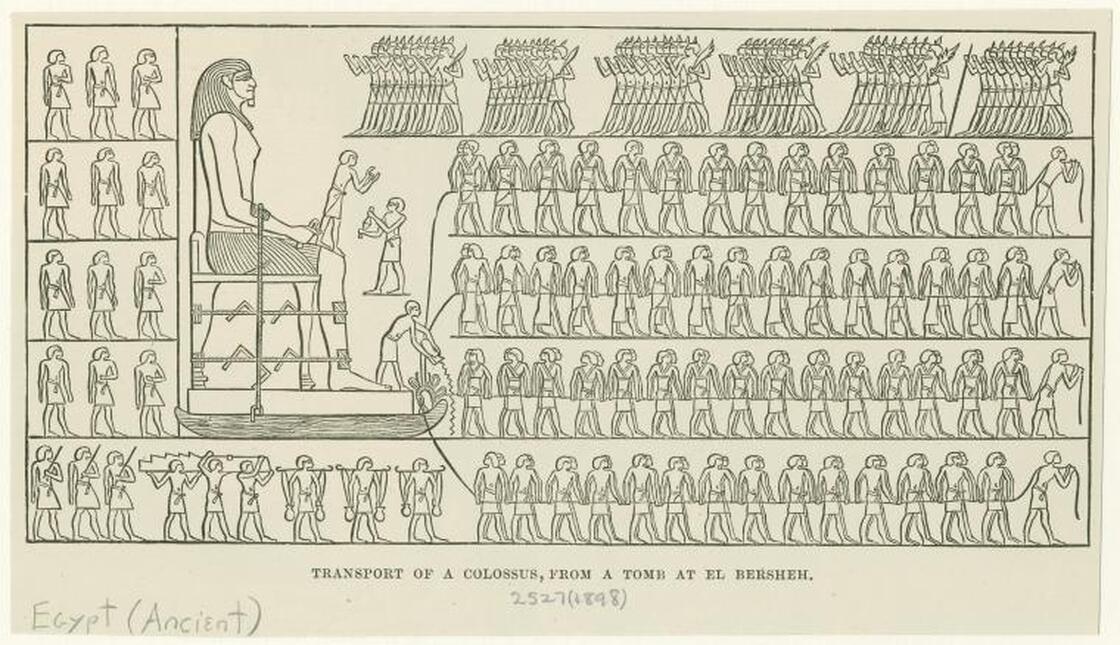

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in Buxton, N.C., was moved almost 3,000 feet inland on July 9, 1999, to protect it from the advancing ocean.Bob Jordan/AP  Judging from a carving found in an Egyptian tomb, experts say 172 men were used to transport the 60-ton Statue of Tehuti-Hetep, circa 1880 B.C. Water was used to lubricate the colossus as it slid along wooden planks.NYPL Digital Gallery

Judging from a carving found in an Egyptian tomb, experts say 172 men were used to transport the 60-ton Statue of Tehuti-Hetep, circa 1880 B.C. Water was used to lubricate the colossus as it slid along wooden planks.NYPL Digital Gallery

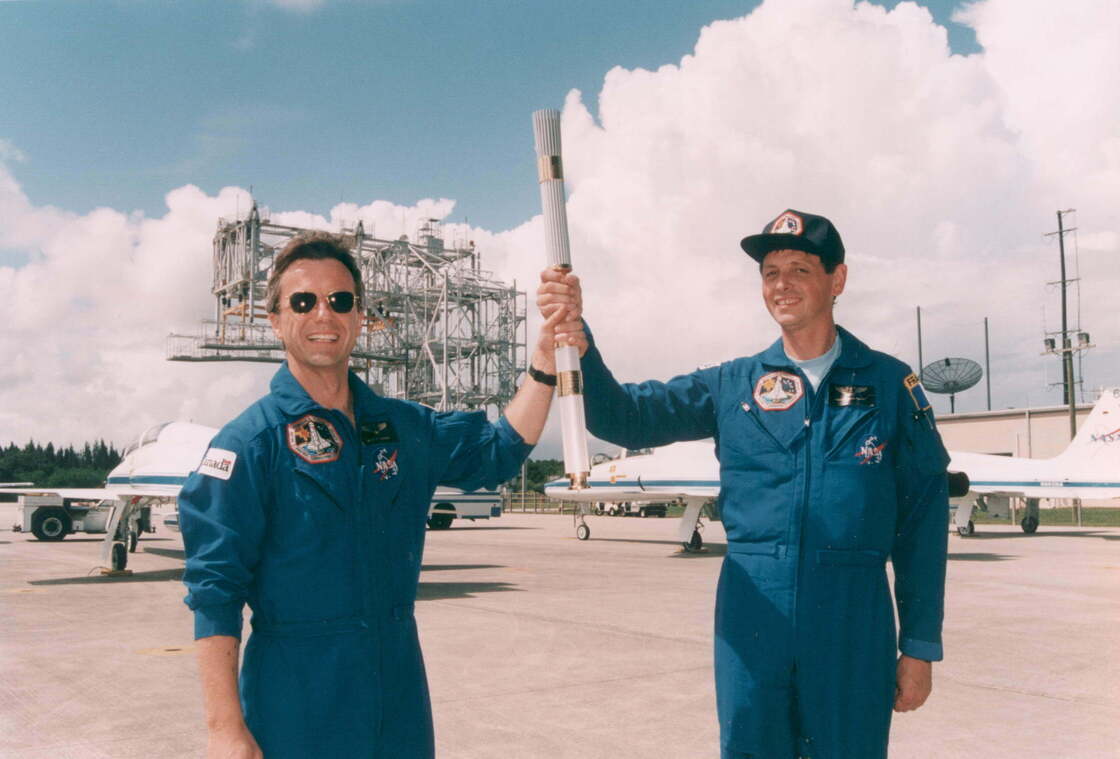

Payload specialists Robert Brenton Thirsk, left, and Jean-Jaques Favier hold the Olympic torch they brought to space aboard Space Shuttle Columbia in 1996.NASA

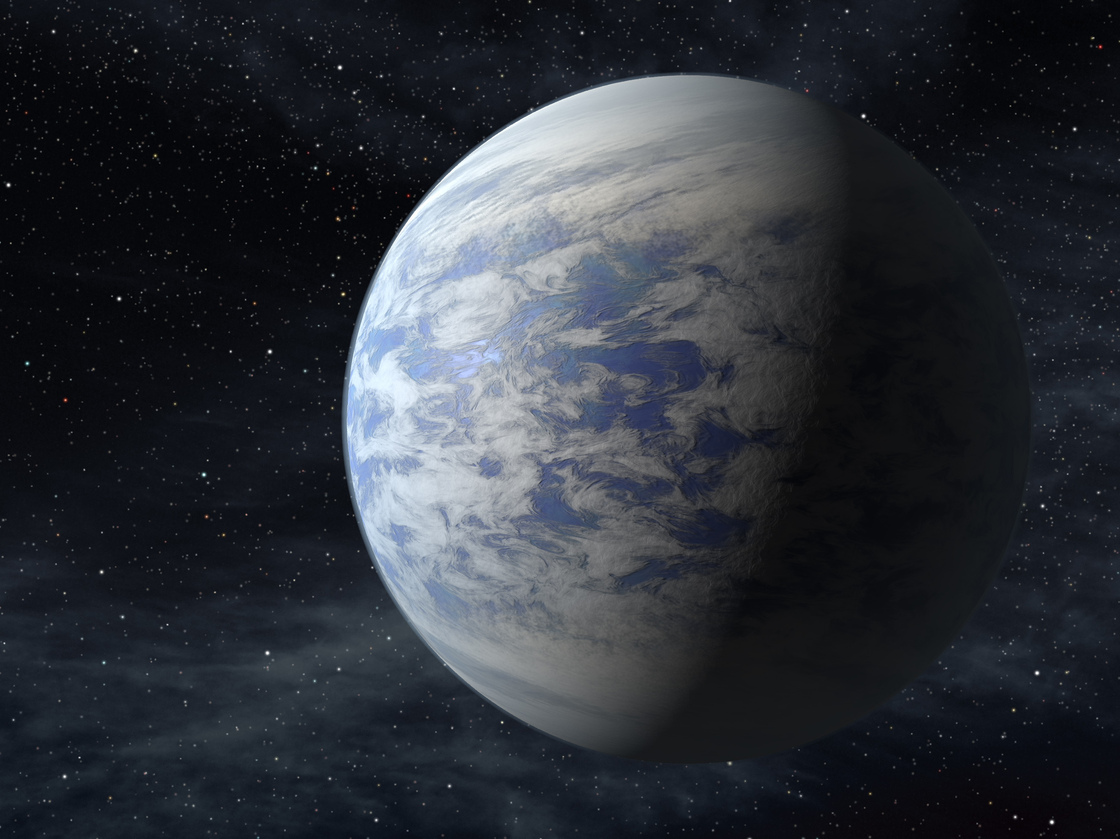

Payload specialists Robert Brenton Thirsk, left, and Jean-Jaques Favier hold the Olympic torch they brought to space aboard Space Shuttle Columbia in 1996.NASA  An artist's rendition of Kepler-69c, a super-Earth-size planet in the habitable zone of a star like our sun, located about 2,700 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus.AP

An artist's rendition of Kepler-69c, a super-Earth-size planet in the habitable zone of a star like our sun, located about 2,700 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus.AP

A large bull moose is inspected by a hunter at a weigh station in Maine.Robert F. Bukaty/AP

A large bull moose is inspected by a hunter at a weigh station in Maine.Robert F. Bukaty/AP  In recent years, pork producers have found ways to keep the animals healthy through improved hygiene.M. Spencer Green/AP

In recent years, pork producers have found ways to keep the animals healthy through improved hygiene.M. Spencer Green/AP  Craig Rowles raises pigs near Carroll, Iowa. The piglets will enter and leave this room as a group.Dan Charles/NPR

Craig Rowles raises pigs near Carroll, Iowa. The piglets will enter and leave this room as a group.Dan Charles/NPR  A rocket carrying the Mars orbiter lifts off from the island of Sriharikota, India, on Tuesday.Arun Sankar K/AP

A rocket carrying the Mars orbiter lifts off from the island of Sriharikota, India, on Tuesday.Arun Sankar K/AP  The PSLV-C25, with India's Mars orbiter aboard, prior to Tuesday's launch at the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in southern India.Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO)

The PSLV-C25, with India's Mars orbiter aboard, prior to Tuesday's launch at the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in southern India.Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO)  Carbon monoxide is an invisible odorless gas that is the leading cause of accidental poisoning deaths in America. Carbon monoxide detectors can alert you to dangerous levels of carbon monoxide. Originally, carbon monoxide detectors were simple opto-chemical detectors that indicated the presence of carbon monoxide by exhibiting a color change when carbon monoxide reacted with a chemical on a white pad, producing a brownish or black color. These detectors do not require an external power source to function, but modern designs use audible alarms to confer a higher level of protection: A opto-chemical or gel sensor interacts with synthetic hemoglobin, darkening in color when carbon monoxide is present and lightening in color when carbon monoxide concentrations are low. A light sensor may be used to detect the change in light levels to sound an alarm. An integrated circuit monitors a sensor, tripping the alarm when concentrations of carbon monoxide are high. The sensor is made from thin wires of semiconducting tin dioxide that rest on an insulating ceramic base. Increasing carbon monoxide concentration reduces the electrical resistance of the sensor, causing the alarm to sound. This is an electrochemical cell that is designed to produce current in relation to the amount of carbon monoxide present in the air. Carbon monoxide is oxidized to carbon dioxide at one electrode while oxygen is consumed at the other electrode. Sulfuric acid is the usual electrolyte that separates the electrodes. The current triggers the alarm or can even be used to quantify the amount of carbon monoxide that is present.

Carbon monoxide is an invisible odorless gas that is the leading cause of accidental poisoning deaths in America. Carbon monoxide detectors can alert you to dangerous levels of carbon monoxide. Originally, carbon monoxide detectors were simple opto-chemical detectors that indicated the presence of carbon monoxide by exhibiting a color change when carbon monoxide reacted with a chemical on a white pad, producing a brownish or black color. These detectors do not require an external power source to function, but modern designs use audible alarms to confer a higher level of protection: A opto-chemical or gel sensor interacts with synthetic hemoglobin, darkening in color when carbon monoxide is present and lightening in color when carbon monoxide concentrations are low. A light sensor may be used to detect the change in light levels to sound an alarm. An integrated circuit monitors a sensor, tripping the alarm when concentrations of carbon monoxide are high. The sensor is made from thin wires of semiconducting tin dioxide that rest on an insulating ceramic base. Increasing carbon monoxide concentration reduces the electrical resistance of the sensor, causing the alarm to sound. This is an electrochemical cell that is designed to produce current in relation to the amount of carbon monoxide present in the air. Carbon monoxide is oxidized to carbon dioxide at one electrode while oxygen is consumed at the other electrode. Sulfuric acid is the usual electrolyte that separates the electrodes. The current triggers the alarm or can even be used to quantify the amount of carbon monoxide that is present.  Here's a picture I took of the hybrid solar eclipse from Uganda on November 3, 2013. Just what is a hybrid solar eclipse? It's a rare type of solar eclipse consists of an annular eclipse that transitions into a total solar eclipse. The eclipse looks like a ring of fire, sparkling with colored beads and jets, that becomes a total solar eclipse, where the sun's corona fans out around a black disc. This happens when the curvature of the Earth intercepts the moon's umbra (shadow), blocking out the entire disc of the sun. The hybrid eclipse was visible in the Atlantic ocean, while I saw a total solar eclipse in Africa.

Here's a picture I took of the hybrid solar eclipse from Uganda on November 3, 2013. Just what is a hybrid solar eclipse? It's a rare type of solar eclipse consists of an annular eclipse that transitions into a total solar eclipse. The eclipse looks like a ring of fire, sparkling with colored beads and jets, that becomes a total solar eclipse, where the sun's corona fans out around a black disc. This happens when the curvature of the Earth intercepts the moon's umbra (shadow), blocking out the entire disc of the sun. The hybrid eclipse was visible in the Atlantic ocean, while I saw a total solar eclipse in Africa.  Happy Guy Fawkes Night! November 5th is Guy Fawkes Night, an annual celebration in the UK commemorating the day that Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives hidden beneath the House of Lords. People lit bonfires to celebrate King James I survival of the plot, eventually leading to a public day of thanksgiving, which of course, is celebrated by lighting FIRE, usually in the form of bonfires and fireworks.

Happy Guy Fawkes Night! November 5th is Guy Fawkes Night, an annual celebration in the UK commemorating the day that Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives hidden beneath the House of Lords. People lit bonfires to celebrate King James I survival of the plot, eventually leading to a public day of thanksgiving, which of course, is celebrated by lighting FIRE, usually in the form of bonfires and fireworks.  Water (H2O) is a polar solvent and each water molecule exhibits polarity. Do you know why?

Water (H2O) is a polar solvent and each water molecule exhibits polarity. Do you know why?